Nature and Wildlife of Andalucia – by Crossbill Guides

To all naturalists, birdwatchers, ramblers, photographers and all other nature lovers, a warm welcome to this page about the nature and wildlife of Andalucia, Spain. This website accompanies two Crossbill nature travel guidebooks – Western Andalucia and Eastern Andalucia. This is an online Crossbill Guide ‘light’ for the armchair traveller. It offers some general insights and images to entice you to visit, plus some practical information, sites and a free route from the Crossbill Guide. Enjoy!

Andalucia (or Andalusia) is one of the most exciting wildlife destinations in Europe. This is is the largest and southernmost autonomous region of mainland Spain. The landscape is extremely diverse and comprises large wetlands at the coast, semi-desert plains in the east, rolling ‘dehesas’ (cork and holm oak savannahs) in the north, and many different types of mountains. Some mountains, in particular the Sierra Nevada, are very high – higher even than the Pyrenees. However, because Andalucia lies a lot further to the south and is much drier, the very structure of the vegetation and landscape is totally different than the Pyrenees.

Andalucia is so large and diverse that we decided it doesn’t fit in a single book – hence we published two Crossbill Guides – one covering the sites in the east, and another one on western Andalucia.

Landscape of Andalucia

Given the huge landscape diversity, it may come as a surprise that Andalucia is topographically quite easy to read. The region is somewhat reminiscent of a giant, open mouth. That mouth faces west. The upper jaw is the immense east-west oriented mountain range of the Sierra Morena, which is part of the geologically ancient core of Iberia. Towards the east, the Sierra Morena connects with the Sierra Betica, which forms the lower jaw. It follows Andalucia’s (and Spain’s) southern to the southwest (rather than south), forming the gaping jaw. At the south-westernmost tip lies Tarifa, a mere 14 kms from the Moroccan coast. The Sierra Betica is geologically much younger than the Sierra Morena, a lot more rugged and consisting largely of marine limestones.

Between these two ranges, forming the tongue as it were, flows Andalucia’s largest river, the Guadalquivir, which flows past Córdoba and Sevilla before feeding Spain’s most important wetland: Coto Doñana. Both the Sierra Morena and the Sierra Betica reach their highest peaks in the east of Andalucia. In this respect, the Sierra Betica is particularly spectacular. Its eastern great massifs is the Sierra Nevada, which reaches 3478 m (Mulhacén mountain). East of the Sierra Nevada the land drops. Here, in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada lies the only part of Europe classified as a semi-desert. Needless to say, it has a spectacular biodiversity.

Wetlands of the coast

On the western coast lie some of Spain’s most impressive wetlands. The Coto Doñana is most famous in this respect, but there are smaller wetlands nearby, most notably the Marismas del Odiel (the saltmarshes of Odiel) and Bahía de Cádiz (the Bay of Cadiz). Combined, these are of unsurpassed importance for wildlife.

Unique within Europe is the temporal nature of Andalucia’s marshes. They hold water from autumn to spring and almost fully dry out during summer. The long period of drought and the extreme evaporation turn the thousands of hectares of shallow water to mud, which cracks up as it dries out. Only small areas which are fed by groundwater or are in direct contact with the ocean will remain wet. In the surrounding hills there are many so-called endorheic lagoons: lakes fed by local rivers that only carry water in winter, and not enough to make it all the way to the ocean. They end in ‘blind estuaries’ – a depression between the hills that fills up in wet winters and dries up during spring. This isolation both geographical (from one river to another) and temporal (from one winter to another) makes these lagoons very specific habitats, that are much more usual in Africa than in Europe.

The flora and fauna of the marismas and endorheic lakes is very special. Many ‘African’ species occur here, like Marbled and White-headed Duck, Purple Swamphen and Red-knobbed Coot, plus lots of exotic dragonflies (e.g. Banded Groundling and Violet Dropwing). The marismas are home to large numbers of waders, but also desert birds like Pin-tailed Sandgrouse and Lesser Short-toed Lark. However, what’s present differs strongly from year to year, as it all depends on the winter rains, which are becoming increasingly unpredictable with climate change…

The Unique Dehesas of Northern Andalucia

Dehesas form a unique landscape that is exclusively found in the centre and southwest of the Iberian Peninsula. Northern Andalucia forms the southern limit of the dehesa, with many millions of hectares found in the Sierra Morena and only few in the Sierra Betica (where they are slightly different).

Dehesa holds the middle ground between a forest and an open steppe. Some people prefer (or even insist on) calling them savannahs as that is what they mostly resemble: scattered trees on grassy plains, sometimes so widely spaced that the landscape indeed resembles African savannahs, but elsewhere, particularly in the mountains, the trees are much closer together and the land resembles an open forest. The trees, mostly Holm and Cork Oaks, are native, but they are regularly pollarded to grow wide canopies that more create shade . The wide canopy protects the soil from erosion and sheep and pigs from the harsh sun. The acorns provide food for the black Iberian pigs that rootle for food here.

Dehesas are very rich in wildlife, particularly birds and insects. This is the land of the Black and Griffon Vultures, the Spanish Imperial Eagle and the Azure-winged Magpie, plus many other widespread Mediterranean species. The original suggests pollarding creates acorns. Accordingly I’d split this off into a the later sentence.

Forests and scrublands

Mediterranean forests and scrublands occur in many different forms and shapes throughout the mountains, particularly the Sierra Betica, but also the Sierra Morena. Nearly all trees are evergreen, with oaks, olives, pines, Strawberry Trees and a large variety of Mediterranean bushes being dominant. Typically, many tree species can easily persist as shrubs and many shrubs can grow up to small trees, making the distinction between forest and scrubland (macchia, or, in Spanish, Monte or Matorral) rather vague. The limestone mountains of the Sierra Betica or often so rocky that scrublands seamlessly merge into rock slopes and rocky grasslands.

It is in this hard-to-pinpoint landscape that many of the reptiles, butterflies and wildflowers occur. Some of these range widely, whilst others are restricted to specific soil types (sandstone, quartzite or limestone). The best places to find such species are those that are not overgrazed.

The coastal sands of the southwest have their own, very typical woodland. Here vast areas of open Umbrella Pine forests dominate the landscape. Between the pines there is a scrubland with many rockroses and wildflowers that are exclusively found along the coast of southern Portugal and western Andalucia.

High mountain forests

Only in the high mountains do you find, in places, classic forests with a more or less closed canopy. Most of them are on north facing slopes. There are some tall oak woods (mostly Portuguese Oak and closely related species) and Austrian Pines, with Aleppo Pinewoods growing on southern slopes.

Ecologically these woodlands are truly special. During the ice ages, Andalucia was a retreat for both Mediterranean and temperate tree species. In the warmer periods, these species moved north again, but a relict remained in the Andalucian mountains, where they evolved in isolation into unique species. Perhaps the most famous example is the Spanish (or Pinsapo) Fir, of which there are just a few forests in the western Sierra Betica. Others are the oak Quercus alpestris (which has an even smaller range) and Pontic Rhododendron, so widely planted throughout Britain and Europe, has a native population along river gorges in the Sierra Betica (more specifically, in Los Alcornocales).

The Hedgehog zone

The highest zones of the mountains are covered in a vegetation of cushion-forming, very spiny dwarf bushes that resemble the vegetative form of a hedgehog. The growth form is an adaptation to high grazing pressure, extreme drought, high solar power but also extreme cold.

Because drought and grazing pressure are not exclusive to the highest parts of the mountains, the hedgehog zone cannot be tied as neatly to an altitude as the vegetation belts in, for example, the Alps. In some very rocky places, this vegetation develops at 1300m, elsewhere only above 2000m.

Due to the isolation from similar high mountains with similar climatic conditions (the nearest ones are in Morocco), nearly all plants are endemics, either of Spain, or shared only with Morocco. There are also many insects (particularly butterflies) that are only found here.

The Semi-Desert Landscape

The stark desert landscapes of the south-east come in various forms. There are gypsum soils, very brittle clay and sandstone deserts and volcanic sites. Most of them do not only have a sparse vegetation because of the dry climate, but also because the soil is very unstable (badlands) or because the soil chemistry poses an extra strain on the vegetation.

As a result, each ‘desert’ in the south-east has its own set of plants, insects and reptiles, making this a very exciting place for naturalists. For birdwatchers this is a hotspot too, with high numbers of Black Wheatear, Black-bellied Sandgrouse and true rarities like Trumpeter Finch and Dupont’s Lark (close to extinction in the area). The great attraction here, beside the stark landscape, is this range of connoisseur species, not so much the diversity per se. The desert is here, as everywhere else, a place where wildlife does not show itself easily.

The naturalist top 10

Ten highlights of your visit to exploring Andalucia

Wild, dry, rocky and remarkably rich in wildlife are the barranco walks in southeast. The landscape is ‘Western-style’, the wildlife consists of Ibex, Black Wheatear, Trumpeter Finch, Bonelli’s Eagle, Common Chameleon, snakes, scorpions and an impressive number of unique wildflowers.

The ‘roof of Andalucia’, the Mulhacen, is spectacular but has a surprisingly gentle topography. This rocky world is riddled with unique, small peatlands, known as borreguiles, with many endemic wildflowers and butterflies.

The karstic plateaux in the limestone mountains, roughly above 1,000 metres are bone-dry, very cold at night and hot during the day. A bizarre world of spiny cushion plants grow here accompanied, of course, by rare birds, butterflies and reptiles.

Some of the highest shifting dunes in Europe are found on the Atlantic coast near Coto Doñana. Some you can visit yourself, but the wildest and most impressive are found in the National Park where a special bus excursion brings you.

Imagine sitting on a slope, with the Straits and, at the horizon, Morocco before you, with hundreds, if not thousands, of birds constantly streaming overhead. That is bird migration at the southern tip of Andalucia. This is one of the largest migration hubs (if not the largest) of the continent: eagles, kites, buzzards, storks, bee-eaters, swifts and countless passerines pass by.

Staying in the Straits, the whale-watching trips from Tarifa can be spectacular, with dolphins and also orca’s present in the narrows. Pelagic birds include shearwaters and storm-petrels.

The broad riverbeds in the mountains may carry only a trickle of water, but that’s enough for many ‘African’ dragonflies. You can walk the riverbeds upstream in search of these colourful gems.

A nearly horizontal layering of soft limestone in an area with significant precipitation has created the most extreme karst landscape of the continent: Torcal de Antequera. Walk down the natural ‘alleyways’ between the ‘high-rise’ pillars of limestone and feel humbled by this natural phenomenon.

The Laguna de Fuente de Piedra is Europe’s largest endoreic lake. This lake, huge after periods of rain; a briny muddy pool after a period of drought, holds many birds, including the second-largest colony of Flamingos on the continent.

The quaint village of El Rocio is the beating heart of the Coto Doñana. Uniquely, this white-housed town only has broad lanes of fine sands, where villagers either pass through on a horse or in a 4×4. The massive church stands right beside the marshes, and birding from the boulevard can be top-notch.

Birds, butterflies and wildflowers – The flora and fauna of Andalucia

A duck with a swollen, smurf-like blue bill, Europe’s only chameleon, one of the world’s rarest felines, drifts of small orchids which’ flowers mimic insects, a lizard that occurs only on a single mountain range and a lark that you can hear but rarely see. These are just a handful of the many truly wondrous creatures that roam the wildlands of Andalucia.

Flora of Andalucia

The Sierra Betica (including the Sierra Nevada and the eastern desert) is one of the 10 hotspots of botanical diversity in Europe. As the Mediterranean region, as a whole is one of the most biodiverse areas in the world, which means that Andalucia ranks among the world’s most diverse wildflower regions, with between 4-5,000 species estimated to occur. Among them are large numbers of endemics – species that occur only in a small area.

Areas with high numbers of endemics are those with a climate and/or environment that is different from the surroundings, thus where species evolved in isolation. In Andalucia, these hotspots are (from east to west) the semi-deserts of Almería province, the Sierra Nevada, the Sierra de Grazalema/Sierra de las Nieves and the western coast (a botanical region that extends into Portugal). In the northeast, the Sierra de Cazorla is brilliant, with endemics like the orchid Orchis cazorlensis, the butterwort Pinguicula vallisneriifolia and the Cazorla violet (Viola cazorlensis).

In Almeria, drought-adapted plants are, of course, most in evidence. However, as due to high evaporation various kinds of salts surface, which means that many species, even in the interior, are (related to) salt-adapted plants. Some very attractive native plants in this area are Caralluma (Europe’s only native cactus-like (stem-succulent) species), Cistanche (a huge, yellow, broomrape relative), desert thumb (a strange, purple parasitic plant) and a high number of endemic sea-lavenders.

The Sierra Nevada has a curious mix of southern high mountain species of the ‘hedgehog’ type (see above) and those that also occur in the Alps and Arctic. Among the latter are saxifrages, bellflowers, gentians and buttercups, some of which are endemic to the Sierra Nevada. Among the hedgehog shrubs are plants like Hormatophylla spinosa, Vella spinosa and ‘Blue Hedgehog Broom’, Erinacea Anthyllis. The latter group is shared with the high mountains of the Sierra de las Nieves and some other ranges, plus the Moroccan Atlas.

The higher mountains of the western Sierra Betica are collectively known as the Serrania de Ronda, which consists of various ranges of which the Sierra de las Nieves and Sierra de Grazalema are the most famous. The flora here is extremely varied, with many endemics, mixed with more widespread Mediterranean species like rockroses, irises, daffodils and orchids etcetera. To name just a few highlights: the aforementioned Spanish Fir, the superb, silvery Viper’s-bugloss Echium albicans, the vine-like birthwort Aristolochia betica and many orchids. Among the latter, Mirror and Yellow-bee are very common, but there are many more, including the very rare and localized Atlantic Orchid (Orchis atlantica).

Lastly, the coastal region has a splendid scrubland flora with many rockroses, a number of endemic bulbous plants and plenty of orchids. A rarity here is the peculiar Green-flowered Narcissus and the Mandrake, both flowering in autumn, and the spectacular, insectivorous Portuguese Sundew (Drosophyllum lusitanicus), flowering in spring and growing in Los Alcornocales.

Mammals of Andalucia

Andalucia’s star mammal is undoubtedly the Iberian Lynx. This is, or at least was until recently, the rarest of the world’s wild cats. This beautiful animal, which once roamed the larger part of the Iberian Pensula, but by the year 2000, only two populations remained: one in Coto Doñana in the southwest of Andalucia, and another in Sierra de Andujar in the northeast of the region. These are still the main areas (particularly Andujar) but reintroductions in Extremadura and Portugal have expanded the population, which is now fortunately no longer in imminent danger of extinction.

The Iberian Lynx is quite different from the European Lynx that once lived across Europe (although now restricted to the east and north of the continent). Just like the Lynx, there is an Iberian Hare and a hedgehog that Iberia shares with North Africa, the Algerian Hedgehog. The Iberian Ibex is also quite different from the Alpine and the (now extinct) Pyrenean Ibex. Iberian Ibexes mostly occur in mountainous regions in the east and south, even at low altitudes in the semi-desert. The Egyptian Mongoose occurs mostly in the lowlands in the west and in the Sierra Morena in the north.

The Straits of Gibraltar is a well-known area for whale and dolphin-watching, including, in summer, the presence of Orcas.

Birds of Andalucia

Andalucia is probably the region with the greatest diversity of birds in Europe. The birdlife clearly has its hotspots. The dehesas and woodlands in the north are home to large numbers of Mediterranean birds: Hoopoes, Bee-eaters, Woodchat and Iberian Grey Shrikes and a variety of warblers, often in very good numbers. This is also the region to search for Black Stork and Black Vulture, which do not breed elsewhere in Andalucia. Other raptors like Black (summer) and Red (winter) Kite are very common, as are Griffon Vulture, Golden, Short-toed and Booted Eagles, with the endemic Spanish Imperial Eagle being more local, especially in the eastern part. Another Iberian endemic, the Azure-winged Magpie is common throughout the north.

In the southwest, it is the marshes that produce the bulk of the avian attraction. All sorts of waders, and herons, Greater Flamingos, Spoonbills, Glossy Ibis occur here, together with Purple Swamphen and smaller numbers of ducks. The highly endangered White-headed Duck occurs here, as does Spanish Imperial Eagle, Collared Pratincole and Pin-tailed Sandgrouse.

On the eastern side of the Guadalquivir, in the province of Cadiz, similar birds occur, but with some additional attractions. The extremely rare and endangered Marbled Duck breeds here, as do some species that are more familiar on the African continent, like Red-knobbed Coot, Little Swift and White-rumped Swift. Following successful reintroduction, the Bald Ibis is also back again.

The Sierra Betica is not quite so attractive, holding a mix of Mediterranean species, but also high numbers of Griffon Vultures and a good population of Bonelli’s Eagle. Black-eared Wheatear is a numerous bird, with Black Wheatear less common.

That latter bird is numerous in the semi-deserts in the south-east, which has a lower bird diversity, but with some very attractive species. Blue Rock Thrush, Pallid Swift, Iberian Grey Shrike, Roller and Great Spotted Cuckoo are more common here than elsewhere, and there are dryland species like Black-bellied Sandgrouse, Stone Curlew and various larks, including the declining Dupont’s Lark. This is the only place in Europe where Trumpeter Finch occurs. Another desert bird, the Cream-colored Courser, also (irregularly) breeds in south-east Andalucia. Finally, the saltpans and wetlands hold important wetland birds, including White-headed and Marbled Ducks.

The high mountains hold fewer birds, but some of them are too important to leave unmentioned. The best areas are Sierra Nevada of course, but the Sierra de Cazorla is also attractive. In the former area, Rock Thrush, Dipper, Citril Finch and Alpine Accentor must be mentioned. Except for the latter, these birds also occur in the Sierra de Cazorla, where you can also find Bearded Vulture and Ortolan Bunting.

Lastly, the bird migration at Tarifa-Gibraltar must be mentioned – one of the greatest bird spectacles in the entire continent. During spring (Feb. – May) and autumn (August – Sept.) a large proportion of western European birds (especially raptors and storks) cross the narrowest part of the straits between Europe and Africa.

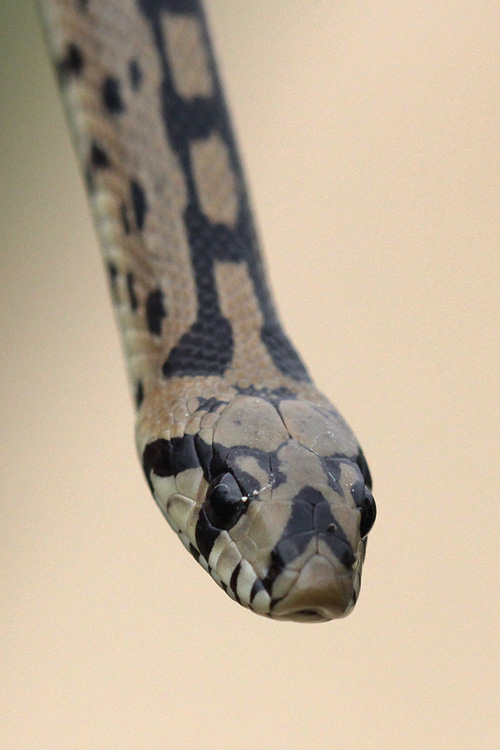

Reptiles and amphibians of Andalucia

There are a great number of reptiles and amphibians in Andalucia. The total number of species is not easy to give, as taxonomic changes have ‘split’ former species into several local forms. Besides a variety of lizards and snakes, there are two terrapins (which live in the water) and one tortoise (living on land). Quite special is the occurrence of the ‘common’ Chameleon, which lives in bushes along the coast and in the eastern Semi-desert.

Butterflies of Andalucia

This is beginning to sound like a broken record, but also the butterfly fauna of Andalucia is extremely rich. Companies that offer butterfly watching holidays (they exist, just less common than the birdwatching variant) always have Andalucia in their programme. Again, it is a mixture of widespread Mediterranean species, combined with Alpine and endemic species in the Sierra Nevada and Sierra de Cazorla, African-Iberian species in the eastern semi-desert and the south slopes of the Sierra Betica. Some highlights include Monarch, Plain Tiger, Two-tailed Pasha, Aetherie Fritillary, Spanish Festoon, Zeller’s Skipper, Desert Orange-tip and Common Tiger Blue, Spanish Greenish Blacktip and Nevada Grayling.

Dragonflies of Andalucia

Throughout the Andalucian mountains there are rivers with an attractive dragonfly fauna. There is a mix of Mediterranean and North African species that reach their northernmost limit in southern Spain. The latter group is now rapidly expanding their range due to climate change. Conversely, the range of these species is shrinking in Morocco.

Among the latter group are sought-after species like Ringed Cascader and Orange-winged Dropwing (both river species). In the northeast (mostly Sierra de Cazorla) they are joined by equally ‘high profile’ species from the west Mediterranean, like Pronged Clubtail, Splendid Cruiser and Orange-spotted Emerald.

Small reservoirs and endorheic lagoons form another great dragonfly habitat with many ‘African’ species. One of them is the Violet Dropwing is common here – it is now widespread in southern Europe, but was until recently only found in North Africa. Others include Long, Yellow-veined and Epaulet Skimmer, Northern Banded Groundling, Black Percher and Black Pennant.

Top 10 species

Ten superb plant and animal species of Andalucia

This Iberian Lynx is, or at least was until recently, the rarest of the world’ wild cats. It preys almost exclusively on rabbits and is most often seen in the Sierra de Andujar, where a small ecotourism logistic has developed around spotting the lynx (Crossbill Guide Eastern Andalucia).

It is hard to choose what the absolute top is among the Andalucian birds, but the White-headed Duck certainly scores very high. This extraordinary-looking bird is endemic to the steppe lakes and small lagoons in the Mediterranean basin, with Andalucia and some areas in Turkey as the main breeding sites.

Chameleons are animals of Africa, Middle East and India, but they also occur along a narrow strip along the coast of Andalucia, where they live in shrubs, with a preference for brooms in the dunes. In the eastern deserts, they are found in barrancos (wadis).

The Sierra de Cazorla has several endemic species and one of them is a sought-after orchid, Orchis cazorlensis. The tall, handsome purple species evolved from an isolated population of Orchis spitzellii and grows in open pinewoods.

The world’s most familiar butterfly is the Monarch, which has a stable an increasing population all along the south coast of Andalucia. This impressive orange-black species originates from North America, but is a strong flier and colonised Andalucia by itself, after its American larval food plant was introduced in the region.

Of the many peculiar plants of Andalucia, the Portuguese Sundew takes the cake. It is a sundew, alright, but its long, pale-green leaves and its stem all the way up to its sepals is covered in glands that produce sticky drops to catch insects. The plant grows on dry rocky slopes on sandstone.

The Trumpeter Finch (named after its amusing call) is an African desert bird that started to breed in southeast Spain around 2000. Currently this is the only population on the European mainland. Beautiful as these birds may be, the new and growing population is also worrisome as it can be considered a tangible biological response to the climate change and desertification of eastern Spain.

The Spanish Imperial Eagle is one of the most beautiful birds of our continent. It breeds exclusively in the southwestern part of the Iberian Peninsula. The eagle has long been persecuted and came close to extinction. Fortunately, protective measures reversed the trend and now the Spanish Imperial Eagle is slowly increasing. Coto Doñana, Los Alcornocales and the Sierra Morena are its haunts in Andalucia.

The Collared Pratincole as a wader that reminds of a tern of giant swallow. It is in many ways a peculiar bird. It breeds in colonies, sometimes large ones, in fields and saline steppes – a rather specific habitats. This bird can be rare and hard to find, but also very common, with hundreds of pairs breeding in a single colony. Andalucia is probably the most reliable place in Europe to see it.

The Bald Ibis is a cliff-breeding, colonial ibis that was extinct in the wild, with the exception of a single colony in southern Morocco and another in eastern Turkey (with partially reintroduced birds). It was successfully reintroduced near Vejer in Cadiz province, where they can be seen on the nest on a sandstone cliff.

Routes and practicalities

Travelling in Andalucia is a delight. The aforementioned landscapes and species can all be enjoyed in the region’s many natural parks. Of particular interest are Sierra de Cazorla, Sierra Nevada, Sierra de las Nieves and Sierra de Grazalema, each with a good infrastructure of trails. For first-time visitors, do keep in mind that in comparison with ‘classic’ hiking destinations like Britain, France, Germany and the Alpine countries, the number of trails in the Andalucian parks are more limited and for the more popular trails, there are some bureaucratic hurdles to take in the form of permits, which can be obtained, usually for free or a low fee, at the visitors’ centres. Our guidebooks provide more details.

The coastal marshes have a good birdwatching infrastructure, but the endorheic lagoons usually don’t. Keep in mind that water levels are crucial for birds, and in dry years, there may be many fewer species present. The same goes for wildflowers following dry winters.

The best routes, both car routes and walking routes, are described in our Crossbill guidebook on Western and Eastern Andalucia.

The books

The Crossbill Guides are the most comprehensive nature travel guides available. Each Crossbill Guide contain in-depth descriptions of the landscape, habitats, geology and all the species groups of the area, plus links to the best routes to see them.

These routes are typically a mixture of walking routes and car routes with stops and short walks. Combined, these routes cover all the sites for birdwatching, butterflies, dragonflies, plants, mammals and reptiles. They are also set out to give you the finest examples of the ecosystems and geological features. In short, everything for nature lovers.

The Crossbill Guide to Western Andalucia covers the territory west of the line Malaga-Cordoba, and includes Coto Doñana, Cadiz and Sevilla Provinces, with the Strait of Gibraltar and Tarifa, la Janda, the nature parks of Los Alcornocales, Sierra de Grazalema and Sierra de los Nieves, and in the north the western section of the Sierra Morena.

The book includes 18 routes (car and hiking routes) plus 28 wildlife sites.

The Crossbill Guide to Eastern Andalucia covers the territory east of the line Malaga-Cordoba, and includes the Sierra Nevada and Alpujarras, Sierra de Huetor, Cabo de Gata (plus coastal marshes), Desierto de Tabernas, Hoya de Baza, Hoya de Guadix, Sierra de Magina, Sierra de Maria, Sierra de Cazorla and Sierra de Andujar.

The book includes 20 routes (car and hiking routes) plus 18 wildlife sites.

The authors

Dirk Hilbers (NL, 1976), set up the Crossbill Guides Foundation and travels Europe to research the guidebooks. This is the 17th guide he worked on. As a biologist, when not in the field, Dirk Hilbers is a free-lance writer and lecturer in the field of nature education and environmental ethics.

Kees Woutersen (NL, 1956) has lived in Huesca for 20 years, working as a nature and bird guide throughout Spain. He runs his own travel company, Aragon Natuurreizen. Kees Woutersen is author of various books on the birds and natural history of the Pyrenees and Aragon, e.g. the Atlases of the Birds of Huesca and Ordesa.

John Cantelo (UK 1950) taught History and Social Studies before semi-retirement allowed him to fo- cus on his other enthusiasm, birds and wildlife, by field teaching for the RSPB. For the past ten years he has helped edit the Crossbill Guides and for rather longer has been a regular visitor to southern Spain. He is an active member of the An- dalucia Bird Society.

Albert Vliegenthart (NL, 1975) works at the Dutch butterfly con- servancy, is arenowned lepidopter- ist, next to being a keen birdwatch- er. Albert co-authored the Crossbill Guide to the Eastern Rhodopes and contributed to insect chapters of most other titles in the series.

Bouke ten Cate (NL, 1985) is an all-round naturalist with a special interest in ecology, history, amphib- ians, reptiles, and mammals. He is also a keen wildlife photographer. Bouke previously co-authored the guidebook to North-east Poland.